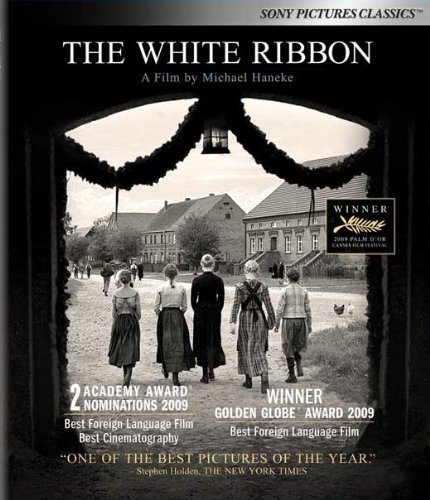

The White Ribbon [Das Weisse Band]

[Guest reviewer Barbara Artson, author of the novel Odessa, Odessa ]

Director Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon (2009) opens in total darkness. We see nothing but hear only the elderly voice of a narrator:

“I don’t know if the story that I want to tell you is entirely true. Some of it I only know by hearsay, and after so many years it remains obscure today, and I must leave it in darkness.”

And so the schoolteacher narrator, now an old man, begins his rendering in a series of flashbacks, depicting the mystifying and horrific happenings that transpired in his youth . There is indeed something rotten in this pre-industrial, ruthless Lutheran culture in a small, agrarian German village shortly before the start of World War I. .

We encounter the Pastor, his wife and children glumly seated at their dining room table. They are arbitrarily sent to bed without dinner, but not before being forced to beg their brutal authoritarian father for forgiveness. A special punishment, ten strokes of the cane, will be meted out and after their penalty “purifies” them, the pastor informs them that their mother will attach a white ribbon for them to wear, only to be removed when they have proven their trustworthiness.

Haneke’s films are not easy to watch, nor are they easy to understand. They confront the observer with aging, infirmity, and death (Amour), sexual perversity (The Piano Teacher), a critique of the media and the ways in which we avoid self-reflection (Cache), and hypocrisy (The White Ribbon). Hypocrisy knows no bounds.

The children, some twenty or twenty-five years later, will return as the Fascists and Nazis of World War II. They might have asked the forgiveness of their callous, fathers, fathers who perpetrated psychic mortification and corporal violence, but the seeds of repressed hatred will break through.

Heneke maintains that his film is not an explanation for the roots of Nazi terrorism, but the schoolteacher’s claim that his tale “may clarify some of the things that happened in this country,” asserts otherwise. It seems plausible that Haneke, who grew up with the shame that plagued many of his generation, wrote under the spell of unconscious survivor’s guilt.

The film, nevertheless, can also speak to us, who, are left in darkness. And weep.

Note: Available on Netflix.

Lenore Gay

Looks interesting. Someday, maybe. Don’t have Netflix.