Queen Charlotte–A Royal Prequel

Some may dislike misconstruing the history of great female leaders–or any history, for that matter, for the sake of entertainment. Queen Charlotte, the newly created Netflix series by Shonda Rhimes, is a rollicking reimagining of the Regency period of King George III and Queen Charlotte. It follows from the three-seasons’ blockbuster series. Bridgerton.

Since watching the opening episode of Bridgerton in which the magnetic Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuvel) presides over a competition to select the most eligible maidens for courting marriage proposals, Queen Charlotte has become a fan favorite.

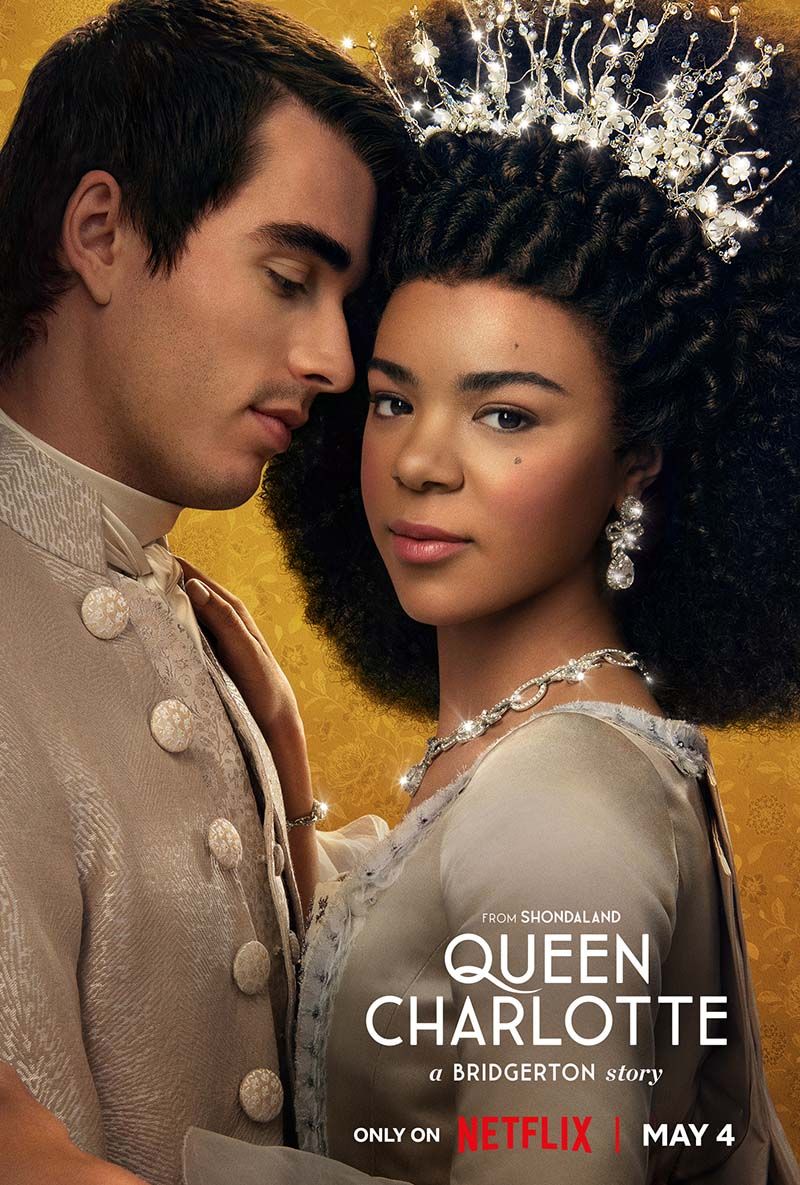

As an alternate history, young Queen Charlotte (India Ria Amarteifio) is Britain’s first black queen–headstrong, beautiful, and very much opposed to her arranged marriage to King George III (Corey Mylchreest), negotiated by her brother and future mother-in-law, Dowager Princess Augusta (Michelle Farley of “Game of Thrones”).

In order to ensure the nobility of her new daughter-in-law and emphasize the young Charlotte’s status– “despite being brown”,– George’s mother engages in the “Great Experiment”, hastily bestowing titles on wealthy Black landowners to integrate the royal court. The pre-existing status quo is adamantly insisted upon by some of the old guard with hurdles imposed upon the new plan.

This royal saga crafts meticulous character arcs for Queen Charlotte spanning several decades, as a story principally of both the younger newlywed queen and also of the royal matriarch she will become. King George III is mainly portrayed as the young smitten royal who is descending gradually into madness, despite his heroic attempts for a cure. (Their inspiring love story is never soapy, in contrast to the Bridgerton series.)

Superimposed upon their love story are two others: the young Lady Danbury (Arsema Thomas) whose backstory is perhaps the most interesting and shocking in her constant fight for independence, both financially and emotionally, while honoring –as her older, more wizened self (Adjoa Andoh)–her close friendship with Lady Violet Bridgerton . And then there are the Queen’s manservant, Brimsley, and the King’s, Reynolds, who are in a loving, necessarily secret relationship because they are gay. Their partnership helps support the love between the King and Queen, in a parallel-tug-and-war of political intrigue.

Queen Charlotte is intricately and brilliantly constructed, a legerdemain of artful character pivots, unexpected betrayal and strength, and brutally honest love in a series of flashbacks between the young lovers and the old. The final scene, a fluctuating montage of the young Queen Charlotte and her old self, with the young mad, breathtakingly dashing King, and his aged counterpart, perfectly bookends the decades-long love they have for each other, in spite of omnipresent opposition.

Kudos to the extraordinary cast, portrayed by different actors in their characters’ youth and in their advanced age. Both actresses who play Queen Charlotte and both who play Lady Danbury deserve recognition for their extraordinary performances . More than the uncanny physical resemblance between the twenty-something selves and their sixty-something counterparts, these four actors absorbed the body language, facial expressions, and vocal mannerisms of each other. Matched scene for scene, they achieve a stellar acting range, mirroring the persona, young and old.

Some pacing drags and sags the middle momentum with perhaps too many lengthy flashbacks, confusing some viewers with the long list of characters to track. But, Queen Charlotte is well-done, and the very best in the Bridgerson stories! Wow!

Availability: Netflix

Note: Whether King George III was ill at the time of the American Revolutionary War is a subject of debate among historians. Some argue that his illness had a definitive impact on the decisions and actions of the British government during his reign, including during the American Revolution. Others claim he was not significantly involved in war policies at that time nor was his mental condition dire.